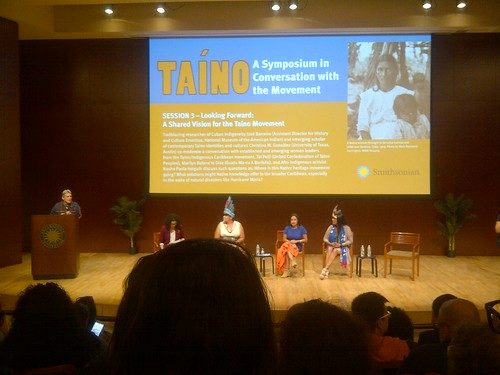

Thanks to a heads-up by meli, I was able to attend an all-day symposium at the National Museum of the American Indian in NYC that is related to their current exhibit, Taíno: Native Heritage and Identity in the Caribbean, which is running until October 2019 and I hope to visit the actual exhibit soon. The exhibit was seven years in the making.

The first real mention in school I remember about Caribbean Indians was in high school. Grade school and junior high school may have mentioned the warlike Caribs chasing out the gentler Arawaks but their focus for the native populations south of the US were the Mayans, Aztecs, and Incas. I don’t remember ever hearing the term Taíno in school. That was a word I heard outside of school (there was also confusion between the South American Arawaks and Caribbean Arawaks, who were similar but not the same and now Taíno is the name used for those from the Caribbean).

In high school, I was told that the Caribbean Indians were all gone. The Spanish had tried to enslave them, which broke their hearts because they were such a gentle people, and they eventually died out. But I grew up knowing that Puerto Ricans are a mixture of white Western European, black African, and native peoples. My mother’s grandmother always told my mother about her Indian blood.

At the symposium I learned about the accepted narrative – the one I was taught in HS – about the extinction of the Taíno and how it was not true. The discipline of study of the indigenous people of the Caribbean was predicated on their extinction. Some Taíno live(d) together in areas of their island (Dominican Republic, Cuba, Puerto Rico, etc) off the beaten path. They have practiced their traditions away from the eyes of the government and the Church. The modern Taíno do not look or live exactly the same as their ancestors, which is one reason why they were dismissed by some, as if the Taíno are not able to adapt like any other people.

The first UN conference on Indians in the Americas was held in Geneva in 1977. The modern Taíno movement grew out of that, so it’s a young movement. We acknowledged that we were meeting on Lenape land.

There were some in the audience who, for me, were dressed towards the costume side. These were not the panelists or others who definitely identified as Taíno.

The symposium was conducted in both English and Spanish and I thought I would be able to understand the Spanish but I was wrong. I should have picked up a headset for the simultaneous translation. The symposium will eventually be in the archives, so I can listen back to the sections where I could not pick up everything said.

Jorge Estévez (Grupo Higuayagua) was in the first panel, which looked back at the movement. He is from the DR and is Taíno. He was attending a powwow in NYC in the late 1980s and ran into some people he knew and was lamenting that he was the last Taíno. They told him there were others. Eventually a group was formed in 1989. There are now several groups of Taíno in NYC. He learned that as early as 1960 there was an Indian drum group called The Brooklyn Drums, who were Puerto Rican and performed at powwows. They wore fringe and added some salsa moves and that’s something the US grassland Indians picked up. When Estévez visited the American Southwest for the first time and hung out with other indigenous people, he saw them pointing with their lips – something he thought of as a DR or PR thing (so did I – I did not know this was an Indian thing). There was a lot of talk about being barefoot, something that is also my preference.

The women wore modern day versions of traditional dress and spoke Spanish. All the older women were referred to as “abuela” (grandmother) and it was obvious that although a lot of men did the talking, the traditions and ceremonies of the religion were being handed down by the women and the healers were mostly the women.

Sherina Feliciano-Santos (Linguistic Anthropologist, University of South Carolina) had a very interesting presentation of the many women she learned from and talked about her language recovery efforts. She is trying to reconstruct the Taíno language. Words like “hurakan” (hurricane) and “hamaca” (hammock) have infiltrated Spanish and English.

Valeriana Shashira Rodríguez (Consejo General de Taínos Boricanos) made a dramatic speech about the earth and being an abuela and there was huge applause and blowing of the guamo (conch shell horn). Elba Anaca Lugo (Consejo General de Taínos Boricanos) and someone from the audience performed for us.

The panel was moderated by Ranald Woodaman (Exhibitions and Public Programs Director, Smithsonian Latino Center).

The second panel had to do with genetic science and genealogy. I was glad that was happening because a woman in the Q&A after the first panel said she had gotten her results back from Ancestry.com, which told her she was 11% Taíno (I rolled my eyes). Deborah Bolnick (Genetic Anthropologist, University of Connecticut) told the audience that there was no way to give a percentage like that. I believe it was Jada Benn Torres (Genetic Anthropologist, Vanderbilt University) that explained how companies like Ancestry.com and 23andMe rely on self-reporting. One woman identified as Cubarican but the genetic tests told her there was a percentage of Ashkenazi Jew in her DNA. Torres said it is because the labels today do not relate to previous labels. Some of her genomes matched the genomes of people who now self-identify as Ashkenazi Jewish, which is in the company’s system. Also, the company may not be looking at the correct place on the genome. One woman in the audience insisted that DNA was more important than cultural identification and she felt there was something to that because of how she related to the Taíno culture and she said she was looking for Taíno sperm and the audience went crazy and it was a while before everyone calmed down.

Bolnick said the absence of evidence does not mean that evidence is absent. Her research is predominately in the southern US.

Hannes Schroeder (ancient DNA specialist, University of Leiden) had a wonderful presentation about the discovery of a 1000-year-old Bahamian preserved tooth from which they could extract DNA. It proves that the Taíno, for the most part, are assimilated but have not been exterminated because modern Caribbean people share DNA with the 1000-year-old tooth, which makes them Taíno and not descendants of imported Native slaves as some historians have suggested.

Carlalynne Yarey Meléndez (Naguake Community) gave a presentation on the indigenous cultural and linguistic educational program in schools throughout southeastern PR. People are coming back to the land.

Jessica Bardill (expert working at the intersection of Indigenous studies and genetic science) showed slides of how the genome of a boy buried in Montana is shedding light on how the Americas were first populated.

The last panel on looking forward was co-moderated by a man and a woman with three women on the panel. Co-moderator José Barreiro (Assistant Director for History and Cultural Emeritus, NMAI) spoke at the podium for way too long, especially considering that he was also slotted to give the closing remarks for the symposium. He lit a little tobacco for our ancestors and said that as early as 1850, the Spanish declared the Taíno extinct because they were weak. Co-moderator Christina M González (emerging scholar of contemporary Taíno identities and cultures, University of Texas, Austin) is a stutterer. And proudly announced it. On the panel were Tai Pelli (United Confederation of Taíno Peoples), Marilyn Balana’ni Díaz (Guatu Ma-cu A Borikén), and Peggy Guatuki Robles-Alvarado (educator, author, performer).

Robles-Alvarado is Dominican and Puerto Rican and practiced faith at home but was also encouraged to study (academically) by her parents. She is now learning to be a priestess in the Lukumi and Palo spiritual systems, which she warned the audience is not something you look up on YouTube or in books and then recreate some ceremonies. It is a long long process. She opened up with one of her poems, “Boca Grande,” which you can find here in full under Instituto Cervantes at Harvard (FAS) Latinx Poetry Reading. The poem is in Spanglish and any big-mouthed woman can relate to it. The poem starts at about 40:00. Someone also recorded her at the symposium, and that’s currently the top video. I do not have speakers so cannot tell if it starts from the very beginning. She told us that you cannot move forward without looking back at your ancestors. It is important to document ourselves. Pelli felt that if there were still more women curers in PR, Maria would have had a different outcome. Díaz said that Maria did force people to go back to a time before many modern luxuries and people had to communicate.

The symposium gave me a lot to think about. How I think about my own heritage and ancestry. I have always considered myself to have Taíno blood but I would not self-identify as Taíno. It was always the white Western European and black African part of my heritage that mostly thought about and identified with. Now I know more and have much more to explore when it comes to my Taíno heritage.

By Carene Lydia Lopez